Before sparks, there are choices – your choices

ATEX is often presented as something technical. As something that lives in standards, directives, and manuals. But in reality, it is about preventing dust and sparks from turning into an explosion – just as concretely as it is about avoiding falls from ladders, burns from chemicals, or cuts in production. And it starts somewhere else entirely: with you.

It’s about you

It is you who choose the equipment. You who must know whether there is a zone. You who press the start button. And it is also you who will be involved if something goes wrong – no matter how many papers, manuals, or CE markings there may be.

ATEX is therefore not only about complying with rules, but about the choices you make in everyday life. It is about whether you use the right vacuum cleaner. Whether someone knows where the dust settles. Whether cleaning is done often enough. And whether there is anyone at all who knows what Zone 22 means – not on paper, but in practice.

ATEX is not a responsibility that can be left to a single person or department. It is about both management’s and employees’ attention and efforts – from daily operations to the overall responsibility of the employer or company management. Although the ultimate responsibility for complying with legislation lies with the employer, it is crucial that everyone in the organization understands the importance of ATEX and how their own actions can affect safety.

How bad can it get – and why zones don’t protect you alone

“Don’t worry – it’s only Zone 22.” That sentence has been said in many production halls. But Zone 22 is not a reassurance. It is a warning.

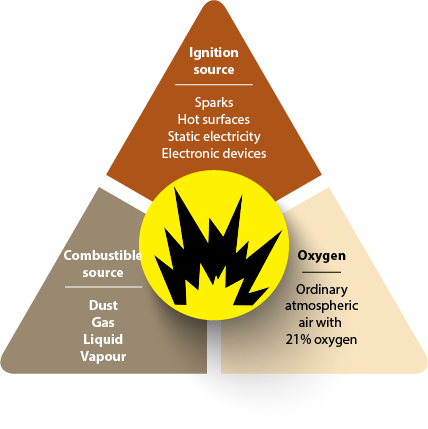

Explosion hazards do not only arise in extreme cases. They occur when three completely ordinary things come together:

- A combustible substance – for example, fine flour dust, sugar, plastic powder, or starch. It doesn’t need to cover the whole room. A thin layer of less than 1 mm in a corner can be enough.

- Oxygen – and we’re not talking about anything special. Ordinary atmospheric air with 21% oxygen – the same air you are breathing right now – is sufficient. No additional supply is needed. The air around us is enough in itself.

- An ignition source – which can be a hot surface, static electricity, a spark from a tool, a motor overheating, or something as trivial as a plug or a mobile phone.

When these three things meet, an explosion can happen. And it does. In Denmark, in Poland, and in all other countries. In daily operations.

It doesn’t have to be dramatic errors: A vacuum cleaner without proper grounding. A hose with too high resistance. A motor in a corner where cleaning is rarely done. That’s enough.

Zones are a help. But they are not a guarantee. Many accidents happen precisely outside the official zones – or in zones that no one has updated since the plant was built.

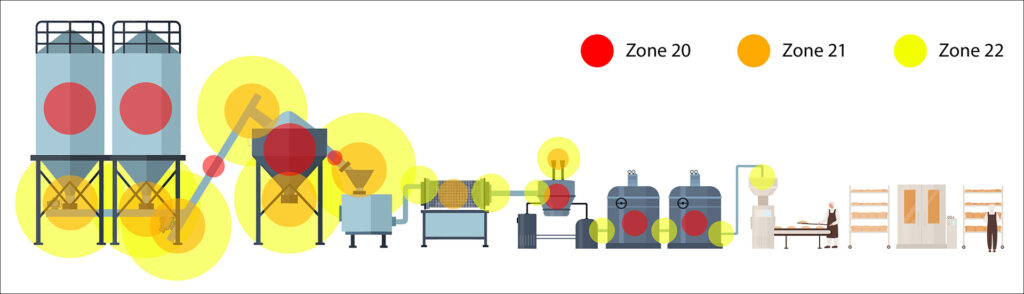

ATEX zones are the result of a risk assessment and designate areas where an explosive atmosphere may occur. The purpose of zones is to illustrate the level of risk of explosion based on the likelihood that a hazardous atmosphere arises and persists. It is important to emphasize that zones in themselves do not protect – they merely form the basis for implementing the necessary safety measures afterwards.

This is where your role becomes crucial. Not as an expert. But as the one who knows what is going on – and dares to take responsibility.

The myths many still believe in

ATEX is a field where half-truths live long. Not because anyone wants to cheat, but because the system is complex, and everyday life demands quick decisions.

Here are some of the most widespread myths – and why they are dangerous:

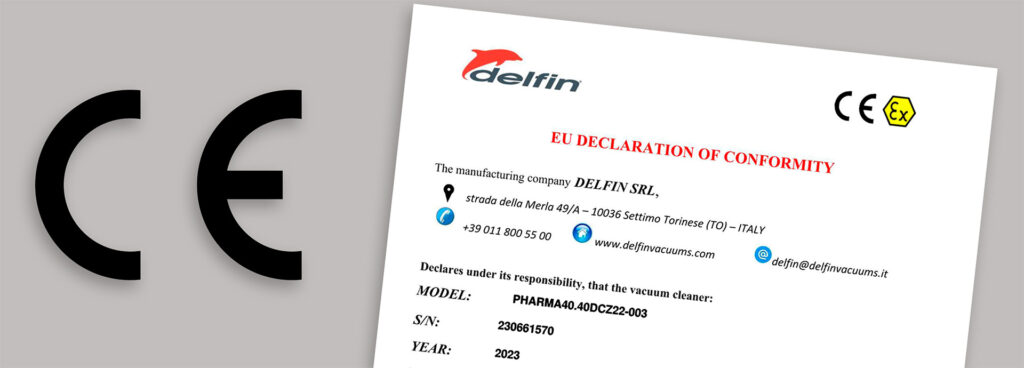

“If it is CE marked, I can use it in the zone”

No. The CE mark means that the manufacturer declares conformity with a number of requirements – but it says nothing about whether the equipment is actually approved for a specific ATEX zone. That requires documentation and, in many cases, a Notified Body.

“Zone 22 is not dangerous – it’s just dust”

Dust explodes. Especially organic dust: flour, sugar, grain, plastic, powder coating, wood. And Zone 22 covers areas where an explosive atmosphere may occur – not where it is constant. It is the unpredictability that is dangerous.

“Our equipment is new – so it is safe”

New equipment can easily be the wrong equipment. We have seen examples of brand-new vacuum cleaners with plastic wheels and missing grounding used in ATEX zones – an obvious safety risk. And even though some manufacturers put an “ACD” label on the machine, it is not an official ATEX approval.

ACD is merely an IEC classification showing that the vacuum cleaner is designed to handle combustible dust in areas without zone classification. If you need documented Zone 20 safety, it requires a full ATEX certificate from a Notified Body according to EN 17348.

“It’s something the HSE people should deal with”

You are part of the working environment. And ATEX responsibility cannot be outsourced if you are holding the hose or choosing the supplier.

The myths persist – and that is why mistakes happen again and again. Mistakes that can be avoided if you dare to ask questions and demand documentation.

What an ATEX zone really is – and how you can make it smaller

Many think that an ATEX zone is a specific room. A space you walk into. But that is not correct. An ATEX zone is a risk area, not a defined place on the drawing.

A zone is considered established where – according to the risk assessment – an explosive atmosphere may occur. The size of the zone can vary significantly, and in practice it can be as small as one meter around an opening or vent, depending on dispersion and persistence of the explosive dust or gas.

Here are some of the most important ways you can make a difference yourself:

- Ventilation: Good extraction and air exchange can remove explosive dust before it accumulates.

- Closed systems: If the process equipment is encapsulated and tight, nothing escapes – and the zone disappears.

- Cleaning up: Dust on shelves, beams, and cable trays is often the most dangerous. Remove it, and you remove the fuel.

- Vacuum cleaners: Use equipment with correct classification and conductivity. This reduces both risk and the extent of zones.

- Routine cleaning: Not just every Friday – but as an integrated part of operations.

- Behavior: No grinding, sweeping, hot work, or drilling in areas with dust – unless it has been assessed and controlled.

- Static electricity: In zones with combustible dust, static electricity or short circuits can be catastrophic. Minimize the risk: No mobile phones or other electrical/electronic equipment unless it is ATEX/Ex-approved for the specific zone. The same applies to your shoes.

The best part? You are allowed to do all this yourself. You don’t need to call in an external consultant to clean up, ventilate, or take responsibility. On the contrary. It is precisely personal responsibility and daily choices that make the difference between a safe environment – and a zone lying in wait.

How to spot the wrong equipment – even when it is CE marked

A vacuum cleaner looks like a vacuum cleaner. A hose looks like a hose. And many times it is only when something goes wrong that one discovers the equipment was not at all approved for use in an explosive environment.

But you can actually learn to spot the right and wrong – even without being an expert. Here are some signs you should know:

CE is not enough

A CE mark only means that the manufacturer declares conformity with applicable directives. But it says nothing about which directives – or how conformity has been achieved.

ATEX equipment requires separate ATEX marking and documentation.

Look for the ATEX mark – and understand it

Correctly ATEX-marked equipment might, for example, have the following designation:

CE 0051 II 2D Ex h IIIC T135°C Db

This means:

- CE 0051: CE marking with indication of the independent test institute, also called Notified Body. In this case, 0051, which is IMQ, the body typically used by Delfin. If the CE mark stands without an NB number, it is self-certification – which is only permitted for category 3 equipment (typically Zone 22).

- II: Non-mining equipment

- 2D: Approved for Zone 21 (D = Dust)

- Ex h: Protection principle for non-electrical equipment (ISO 80079-36/-37). The equipment is designed so that potential ignition sources cannot occur during normal operation or single fault conditions. Used, for example, on mechanical components, pumps, or ventilation parts without electrical circuits. For electrical vacuum cleaners, Ex t (tb/tc) – protection by enclosure – is normally used instead.

- IIIC: Suitable for conductive dust (e.g. graphite, aluminum)

- T135°C: Maximum surface temperature

- Db: Equipment Protection Level (EPL) for Zone 21

• Da = Zone 20 (highest safety level)

• Db = Zone 21 (medium)

• Dc = Zone 22 (lowest)

OBS: If the equipment is certified by a Notified Body, this must appear with a four-digit number after the CE mark. The four-digit NB number shows that a Notified Body has been actively involved in the conformity assessment – for example, through product verification or production quality control.

Absence of an NB number may indicate self-certification, which is normally only permitted for category 3 equipment (typically Zone 22).

Examples:

Delfin: CE 0051 (IMQ)

Tiger-Vac: CE 0081 (LCIE Bureau Veritas)

Depureco: Some models are CE 0080 (INERIS), while others are self-certified and have no NB number.

If a vacuum cleaner is only marked with “CE” and “ACD”, without the extended ATEX documentation, it is not ATEX-certified – and therefore must not be used for vacuuming combustible materials in explosive atmospheres.

Is the equipment tested by a Notified Body?

When a vacuum cleaner handles combustible dust, an internal Zone 20 is always formed – regardless of where it is located.

Zone 20 typically occurs inside equipment such as silos, screws, vacuum cleaners, and the like, where there can constantly or frequently be an explosive dust atmosphere. This zone requires that both electrical and non-electrical equipment be type-approved by a Notified Body such as IMQ or TÜV.

Zone 21 externally requires the same. Only Zone 22 externally may in certain cases be self-certified.

But here the error often occurs:

A vacuum cleaner may well be approved to be placed in a Zone 22.

But: If it vacuums combustible dust, it creates an internal Zone 20 – and that requires a Notified Body certification.

Many therefore use ACD vacuum cleaners in situations where equipment with documented Zone 20 certification is required. ACD is not an official ATEX approval and cannot replace a full ATEX certificate from a Notified Body when internal Zone 20 safety requirements must be documented.

Hoses and couplings – the overlooked weaknesses

Hoses and couplings can be critical if they do not dissipate static electricity. According to EN 60079-32-2, the entire vacuum cleaner’s frame, motor housing, wheels, etc. must have a total resistance to earth of ≤ 10⁶ Ω. And according to EN 17348:2022, parts in direct contact with the dust stream – e.g. hoses, gaskets, and filters – must have a resistance of < 10⁸ Ω.

Hoses with too high resistance, plastic couplings without dissipation, or metal parts without equipotential bonding can build up charge. These ignition sources are invisible – but deadly.

In short: If you cannot document that the requirements are met, you have no proof that the equipment may be used in ATEX zones. And then the responsibility is yours – not the supplier’s.

The responsibility no one has told you that you actually have

Many who work in industry have never received ATEX training, and those who have may have forgotten most of it. Directives and standards are heavy work, and if they are not part of daily routine, they are quickly forgotten. But if you are holding the hose, pressing the button, or ordering the next machine, the responsibility is still yours – even if no one has said it aloud.

ATEX is not just a matter for safety personnel and technical advisors. It is part of your everyday life if you:

- work in areas with dust, vapors, or powders

- choose or use electrical and mechanical equipment

- are responsible for operation, maintenance, or procurement

- carry out cleaning, ventilation, or service tasks

Many incidents happen because no one has felt responsible. Or because people assume that “someone else” is in control.

But there is no “someone else.” There is you – and your choice in the situation.

And the good news? You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to know when to pause and ask questions:

- May this be used here?

- Do we have documentation?

- Is there a risk of dust accumulation?

- Should we have it assessed – or just clean up?

Responsibility is not a burden. It is an opportunity to avoid mistakes before they become dangerous. And it starts with someone daring to say it out loud.

How to move forward – without drowning in directives

It can feel heavy. Paragraphs, markings, standards, concepts. ATEX can seem like a jungle. But it doesn’t have to be. You don’t need to learn the entire rulebook by heart. You just need to know where you stand – and what you can do yourself. And you don’t have to wait – you can start today.

Here is a simple 8-step guide to get started – without compromising safety or legislation:

- Start with the material

Check the datasheet for the product you are working with. Does it say that it is combustible? Potentially explosive? If in doubt – contact the manufacturer. Often they can tell you which ATEX zone their product typically creates. And if they can’t, then send us your datasheet – we will be happy to help.

- Assess the amount and frequency

How much dust do you see? How often does it occur? Is it constant (e.g. during emptying or mixing), or does it occur rarely? This matters for which ATEX zone may need to be defined.

According to EN 60079-10-2 (Annex A, indicative) the zones can be illustrated with typical times per year:

- Zone 20 = > 1000 hours

- Zone 21 = 10–1000 hours

- Zone 22 = < 10 hours

The numbers are indicative and should not be regarded as fixed limits, but as a tool for risk assessment.

Source: EN 60079-10-2:2015, Annex A.3

- Locate the dust physically

Take a walk. Where does it settle? Where does it come out? Take pictures and notes – they will be important later as documentation and for the zone map.

- Find ways to limit emissions

Can you encapsulate the process? Improve ventilation? Move material handling? Small changes can reduce or completely eliminate the need for zones.

But be aware: Incorrect or excessive ventilation can create airflows that spread the dust to other areas and thus expand the zone.

Source: EN 1127-1:2019, sections 6.4.2–6.4.3

- Postpone cleaning – but plan it wisely

Do not use brooms, cloths, or compressed air. That stirs up the dust and increases the risk. Do not use ordinary vacuum cleaners in areas where explosive dust may be present. Plan cleaning when you have clarity about zones and correct equipment.

- Make a preliminary assessment of zone type

When you know the material, amount, and frequency, you can form a preliminary assessment – as described in step 2. It is not a final classification, but it is a good starting point.

- When you know the zone – then choose the correct equipment

Only now does it make sense to choose ATEX vacuum cleaners, filter equipment, or other. Use the classifications actively – and be critical of CE marks without documentation.

- ATEX zones are not permanent – follow up

When you have optimized processes and cleaned up, reassess the situation. ATEX zones are not static – they must be re-evaluated regularly. Also remember that a Zone 21 often entails a Zone 22 at the periphery. Know the boundaries and document them.

In short:

You are allowed to act. You are allowed to document. You are allowed to improve.

What you do now can save the company from both dangers and expensive consulting rounds.

And most importantly: It is allowed. It is responsible. And it is the beginning.

You are almost there – now documentation and visibility are missing

If you have come this far, you have understood the risk, taken responsibility, and started acting. That makes you part of the solution – and not just someone hoping others will fix it.

Now only the final steps remain: documentation and visible behavior.

Documentation – the law requires it

There are differences in how ATEX documentation is handled in Denmark and Poland – but common to both countries is that the documentation must be written, realistic, and adapted to actual conditions.

In Denmark:

- ATEX conditions must be included in the company’s workplace assessment (APV). It can also be drafted as a separate ATEX-APV.

- If there is a risk of explosion, an Explosion Protection Document (ESD) must be prepared with:

o zone drawing

o risk assessment

o documentation of equipment used - It is not a requirement to have it prepared externally – the important thing is that the document exists and realistically covers the conditions.

- The basis is found in Executive Order no. 268 of 2005.

In Poland:

- Companies must prepare a Dokument Zabezpieczenia Przed Wybuchem (DZPW) if an explosion hazard may occur.

- The DZPW must include:

o classification of hazardous areas (zones)

o assessment of explosion risk

o description of technical and organizational measures - The documentation is required under the Regulation of the Minister of Economy of 8 July 2010.

- It is kept internally but can be inspected by Państwowa Inspekcja Pracy (the Polish labor inspectorate) or fire safety authorities.

Make the zones visible and safe

Once you have defined where the zones are, make them visible and understandable to everyone. It is not just about rules – it is about prevention:

- Mark the zones clearly on floor and wall (e.g. with color coding, tape, sign, or QR link to your zone map)

- Put up signs: What is not allowed in the zone?

– Examples:

• No hot work (grinding, welding)

• No spark-producing tools

• No mobile phones

• Only approved footwear and equipment - Inform colleagues and suppliers: They must know the zones – and what applies.

It doesn’t have to cost much. But it shows that you have understood the seriousness – and created an environment where ATEX is not a danger, but a part of your culture.

Need concrete guidance?

We help companies every week with:

- understanding and defining their zones

- choosing correct equipment for dust and zone

- avoiding pitfalls with marking and myths

- preparing documentation and a plan for ATEX-safe operations

We do not perform formal zone classification – but we help you take responsibility and get an overview before involving others.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact us.

Thomas Lyngskjold

August, 2025